Change(d) the Name

(Originally published in RezX Magazine, May 2014 in a condensed form. Online now, print copies available soon!)

It has been a month since Saskatoon Public Schools voted to change the name and logo of my high school’s sports team, the Bedford Road Redmen. It has been nearly two decades since the last request for a name change was shut down in 1996. It has been only one week since I lost yet another high school friend who said she would be a “proud Redmen” forever, regardless of how many Native classmates found it offensive.

Indigenous people are not the only groups subject to the mascot treatment, but it certainly seems a bit more absurd when other groups are the focus of the “honor”. Take for example the Coachella Valley “Arabs”, or the Pekin “Chinks”. Why do these seem so strange, while hundreds of Native mascots in North America are normal?

The Pekin Chinks 1971 “Chink and Chinklet”.

One argument our group dealt with countless times was: “It’s just a name, it’s just for fun. Don’t you people have bigger issues to deal with?”

If it were only about a high school sports team name, the backlash against us would not have been so violent.

When the University of Regina cheerleaders took pictures of their “Cowboys and Indians” party, one depicting the girls dressed as “cowboys” playfully aiming their fingers as guns at the girls dressed as “Indians”, it was about more than just a party.

When you walk into a store at Halloween and see overpriced costumes like “Sexy Squaw” and “Indian Princess”, while Indigenous women remain the group most likely to face sexual violence in the US and Canada, it is about more than just a costume.

And, far from being just a name, the Bedford Road “Redmen”, Washington “Redskins”, Moose Jaw “Warriors”, and Chicago “Blackhawks” are products of white supremacy; stories told about us while excluding our voices. While it seems like a small issue on the surface, challenging inaccurate depictions of Native people is a big step toward a better life.

At Bedford, the Redmen logo was used for sports, while a diamond-shaped emblem was used for academics. This is why I don’t accept the claim that Indigenous people are only “warriors” or “braves” to be an honor. The relegation of Indigenous people to the realm of the physical has its roots in centuries of European philosophy.

The use of Indigenous people as sports mascots is frequently justified by using so-called positive stereotypes: Indigenous people are brave, they are warriors, they are skilled hunters, and they are in touch with the land - the sort of characteristics possessed only by non-human animals and primitive groups of humans. The sort of characteristics that make the best sport mascots.

The thing about “positive” stereotypes is that they are still stereotypes, and thus, still function to deny individuality to members of marginalized groups and keep them marginalized. Thought of as lacking any individual agency or autonomy as slaves to our genetic predisposition as animalistic, savage warriors, we are unable to transcend the physical and denied access to rationality. We are turned into “beasts” - unable to self-govern, non-industrious, and dangerous. Perpetuating this view of Indigenous people insures that the invasion of land and assuming ownership of resources is justified. Residential schooling is justified. Injustice, cruelty and disregard for our lives is justified.

Refusing to put up with racist sports team names, mascots, and logos is a declaration that we are more than disposable stereotypes with tomahawks in John Wayne stories where the injuns always lose. We are teachers, students, lawyers, writers, artists, musicians, workers, and activists. We are capable of doing well in schools and universities while still holding on to our traditional knowledge - recognizing that the two are not incompatible, and that Indigenous knowledge ought to be (and already is) present in Western academic institutions. We are members of unique communities and we are individuals.

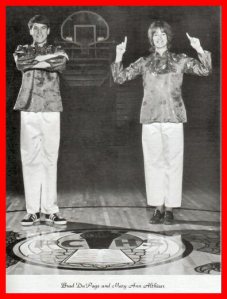

The hardest part of this work is listening to the stories of Aboriginal youth who dare to speak out against stereotypes, and faced ostracism as a result. In January, a student from Oskayak High School (and a dear friend of mine) stood up at Bedford Road’s basketball tournament with a sign that said, “We are people, not mascots” (I painted that logo, by the way, and cringed while doing it). He was booed by hundreds of Bedford Redmen basketball fans before being escorted out of the school, demonstrating that there is a certain type of “red man” that is acceptable (a cartoon) and one that is not (a living person with a voice). To me, that is a real warrior.

On May 31, Bedford Road will be having a sale of Redmen memorabilia. In response, a teacher said, “Isn’t it sick that they are profiting off of this one last time? That logo is like a swastika to me. It is a symbol of hate.” It would be a nice gesture if Bedford uses the proceeds of the sale toward Aboriginal educational initiatives. The name and logo are gone, but the damage is not undone.

I still have my Redmen gym clothes. I will not sell or destroy these little pieces of racism, but keep them in a drawer as a reminder that as Aboriginal peoples, we still face stereotypes from those who refuse to see us as individuals, but there is always a way to overcome. That there has to be a way. We convinced Saskatoon Public Schools to change the name after they realized we wouldn’t give up, âhkamêyihtamowin: perseverance. Even after so many have predicted our demise, we are still here. Now it’s time to tell our own stories.

Thank you for this great reflection. I was already thinking as very awkward the name and logo of sport teams at College Ahuntsic in Montréal, Québec (Indiens), but you gave me the courage to say something about it and try to change it.