Today - February 9, 2022 - marks four years since the colonial court acquittal of Gerald Stanley for the killing of Colten Boushie. Still, few of my days pass without Colten and his family coming to my mind, and I know the same is true for many of our relatives on the prairies and beyond.

At the time of the acquittal, I was away from home in Toronto. I remember my tweets and texts exploding, and then my phone ringing: it was my best friend, a dene writer from Northern Saskatchewan, though neither of us could speak a word. We communicated our heartache through hours of tears as more information came in, eventually ending the call with “I love you”s.

I stayed up all night to help organize a rally for the next day in Nathan Phillips Square in Colten’s memory. Back home in Saskatoon, a thousand people showed up in front of the courthouse. Across Canada and around the world, innumerable actions were held, each one a significant act of refusal; an international witnessing and a charge of ongoing genocide.

I wrote this essay on being outside the courtroom during the preliminary hearing, which took place in January 2018 in North Battleford, Saskatchewan.

The Battlefords are a site of historic and continued life, gathering, and resistance for Nēhiyaw, Métis, and Plains Indigenous peoples. In composing this piece, I wanted to document the ways our communities and nations have always resisted hatred with righteous rage and anti-colonial love.

We miss you, Colten. Today and always.

Twelve Thousand Moons

Erica Violet Lee

When I am old, I will tell you I remember dancing. I remember morning ceremonies at the Squamish, xʷməθkʷəy̓əm, Tsleil-Waututh waterfronts, shutting down malls in amiskwaciwâskahikan, organizing all night in Iqaluit, and the Chief setting up camp by that funny little concrete flame.

I will tell you about the day we danced in front of the old rail station in North Battleford, our drums shaking the spikes from the tracks and eventually shutting down the courtroom inside. When we sang those love songs louder after the cops told us to settle down so the trial could continue, it was mourning and celebration all in one. That’s what most of us did those early days: counting our time in breaths, breathlessness, and how many round dance songs before we hit the ground.

I will tell you I remember every time they said our starvation was natural and our dispossession was progress. Every time they said our freedom was impossible, and how this made us want it even more. I remember how upset they were when we started growing tobacco and vegetables in the plots of wasteland they had reserved for gas stations.

When I am old, I will tell you I remember refusal. I remember walking around what used to be the financial district in Dish with One Spoon and re-imagining it as our own, once more, feet sore from marching but unwilling to give in to sleep. I remember the days our people were locked up for fighting pipelines, for graffiti, for sex, for smudging, for living. I remember the night we broke them out and brought them all home.

When I am old, I will tell you I remember learning to twist copper wire snares from big, rough hands that didn’t need hide mitts in the bush but wore them anyway, just to show off that someone cared enough to keep those hands warm. I remember catching my first fish, taught exactly how to knock a pike on the head so it didn’t suffer long; this is how we cherished kindnesses in a world that afforded few.

I remember the Red River and Red Rising Rebellions. I remember the earrings my sister made me with beads the color of northern lights to wear to that extravagant party with Nēhiyaw philosophers, Dene physicists, and Anishinaabe poets after the first time a Métis went into outer space. We danced then, too, and I remember waking up by the fire after a bit too much strawberry champagne, surrounded by a circle of friends telling their re-creation stories with shadow figures on the wall.

When I am old, I will tell you I remember learning about freedom beyond anthems and passports. And how we never went back once we knew the kind of love bound only by shorelines, prairie skies, and forest floors.

The dream of these twelve moons, just like the twelve thousand before and after, is freedom. And one last thing, before I forget, remember: our memories contain every future, every sunrise, you will ever need.

at the preliminary hearing in the Battlefords, Saskatchewan, January 2018.

—-

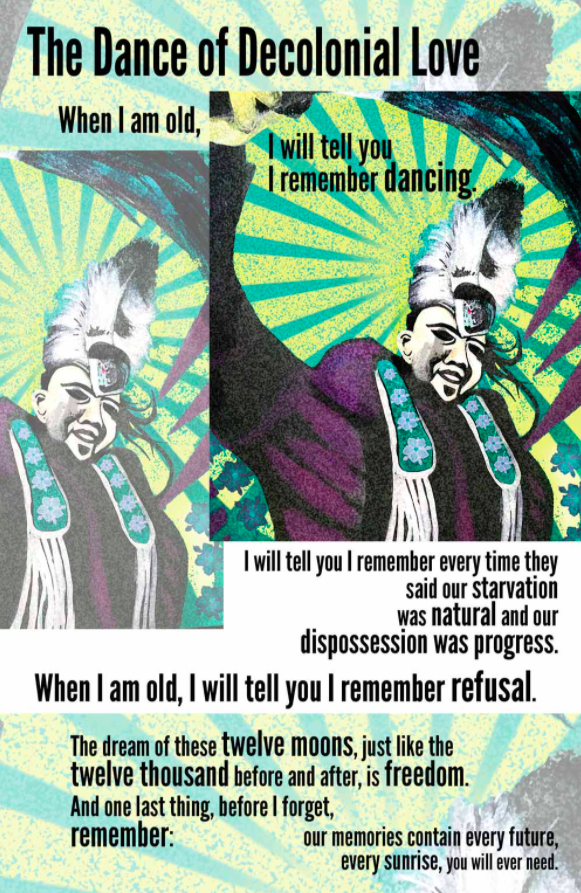

“Twelve Thousand Moons” was originally published as part of the Graphic History Collective‘s Remember | Resist | Redraw series. Angela Sterritt contributed artwork to accompany my words on this poster, entitled “The Dance of Decolonial Love” (PDF). This entire poster project is open-source and each one is available for classroom and educational use.