“The Indigenous person engages in philosophy by thoughtfully examining the world. The outsider examines Indigenous philosophy by thoughtfully interacting with the Indigenous philosopher.”

— Thurman Lee Hester Jr. and Dennis McPherson, “The Euro-American Philosophical Tradition and its Ability to Examine Indigenous Philosophy”1

With the release of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Report on residential schools in June 2015, “Indigenizing the Academy” is a hot topic in Canadian universities. As institutions explore the introduction of Indigenous content, we have to question what is defined as Indigenous content, who this content serves, and how the pursuit of “indigenizing the academy” can easily become exploitative.

In 2013, I helped put together a new syllabus for an Indigenous Philosophy class at my university. The philosophy department wouldn’t consider allowing someone without a PhD in philosophy teach this course, but pairing an Indigenous undergrad with a white philosophy professor was, apparently, acceptable. (Oh, the power dynamics.) Aware of the limitations of our knowledge, we created a course that was largely guest speakers: a roster of amazing Indigenous scholars and elders. This couldn’t have been done, practically or ethically, without immense support from the Indigenous Studies faculty.

Many canonical European philosophers - Hegel, Kant, Locke, to name a few - saw Indigenous peoples as lacking agency, and incapable of intellectual thought. This is the history that the discipline of philosophy inherits, but far from being a legacy, philosophy is still used as a way to signify whose knowledges are legitimate and whose are invalid.

The portrayal of Indigenous thought as simplistic, primitive, and unarticulated is key in the erasure and justification of genocide.

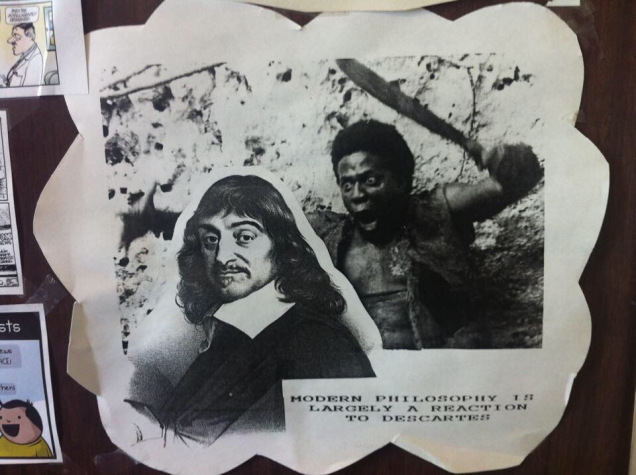

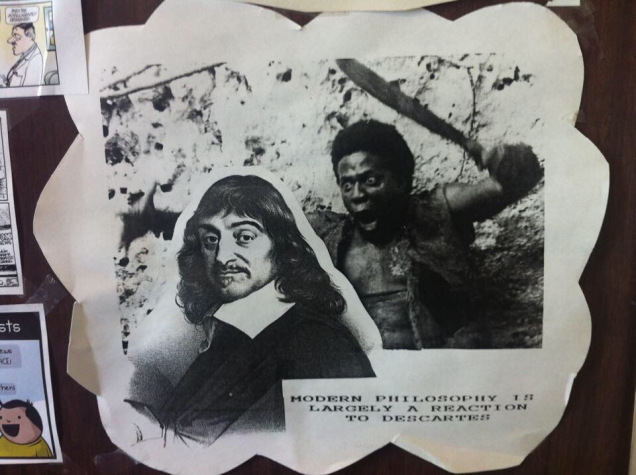

This picture was taped to the door of a professor in the philosophy department at my university.

(a photograph of a collage of Rene Descartes, juxtaposed with an image of a black man with a machete, so it appears that Descartes is about to be attacked. Text reads: “modern philosophy is largely a reaction to Descartes”)

A Case Study in Classroom Colonialism

Originally, “Indigenous Philosophy 115” was registered as a course by a white professor in the philosophy department. Multiple Indigenous scholars on campus were curious about this class and contacted the philosophy department, but attempts for clarification regarding his experience or qualifications to teach Indigenous content proved unsatisfactory.

This September, I decided to sit in on the class with a few friends, and I took notes on the experience. (A bit of ethnography, if you will.)

Field Notes: Indigenous Fauxlosophy

Day One: September 4, 2015

1. The professor starts the class, “Philosophy is not so much about learning about history, I want to know what you think and feel about the issues”. A statement like this wouldn’t fly in any other philosophy class, of course. While universities may have just “discovered” Indigenous philosophy, these knowledges are vast, complex, unique to nations, and well-understood by community knowledge keepers.

2. “I like going into a class where I can make my own views. Not just memorize this, memorize this. Well, what about ME?” The hard, selfless life of a white guy in philosophy. Never hearing your history, having your knowledges mutilated by outsiders. Wait, what?

3. “In philosophy we study pros & cons, different views. In my ethics class I taught about homosexuality from both pro & con perspectives.” Some students shift uncomfortably in their desks. In philosophy, so often, the lives of marginalized people are reduced to thought experiments. (I wrote about this here.)

4. “The United States didn’t give any title to Natives. They have reservations, that’s it.” A fundamental misunderstanding of the nature of Indigenous sovereignty.

5. We begin the reading. He reduces the story to how the Penobscot author is lacking self-esteem as a Native in a “new place”. All the vast, beautiful, endless worlds of Indigenous knowledge to choose from & he starts the entire class with how Native women apparently “lack self-esteem”.

6. “Eunice was from Maine, Penobscot, an group that has been there - well, since contact […] which is impressive because not many Natives were there. How many Natives are in Manhattan now? Washington D.C.? None!” False.

7. The professor’s explanation of Indigenous governance: “It was like university, faculty get together with Robert’s Rules of Order, everyone had input.” False. Bonus points: I know a lot of faculty who would disagree with that assessment of democratic university governance.

8. The last note I wrote down: while discussing the benefits of an authoritarian model of government: “People feel valued when someone takes charge […] there’s less bumbling around, things get done, houses get built”. (If you’re interested in substantial discussions of how First Nations are confronting lack of safe housing as a real problem rooted in systematic underfunding, check out the One House, Many Nations project.)

Day Two: September 9, 2015

We discuss capitalism. A back-and-forth interaction:

A student raises the issue of the Oka Crisis. The professor’s response: “Well the issue there was a golf course. That was local.”

Student replies: “The issue was colonization.”

The professor replies: “Colonization and a golf course. […] those are very particular disputes. Like New Calendonia. That’s a little area of land that the people of Six Nations want, but the people in that area don’t want to give up.”

“I don’t think the author is thinking just of Indigenous people as suffering. There’s all sorts of people who are suffering.”

Student replies: “Isn’t this an issue of white supremacy?”

The professor says: “Why would you say white supremacy? […] Global capitalism now is racially neutral. […] Capitalism goes beyond issues of colonialism or race.”

Day Three: September 11, 2015

We spend the entire class studying the new-agey, super questionable course text and the words of a woman who claims to be Seneca. A quick Google search finds little content other than discussion of plastic shamans. I raise this issue at the end of the class; the professor’s response is “well, she says she’s Seneca!” I wish I had Kim TallBear or Joanne Barker here beside me, right now.

[[Update, Nov 10: A woman who is part of the author’s community contacted me to vouch for her. Unfortunately, it appears that some facilitators are carrying out “Native American” teachings in her name (in workshops that cost hundreds of euros) now that she is passed. As a non-Seneca, it’s not my role to name the author here.]]

Day Four:

Research discontinued for the sake of my wellbeing and the value of my time.

The Histories of Erasing & Co-Opting Indigenous Knowledge

There is nothing new about white academics being paid to teach about Indigenous people. As Choctaw historian Devon Mihesuah writes, “The greatest body of acceptable telling of the Indian story is still in the hands of non-natives”.2 While some departments may develop Indigenous content courses based on genuine desire for social justice, there are many benefits and rewards for white settlers who decide they want to teach “Indigenous content”. Suddenly, these settlers become the resident “Indigenous experts”, consultants for all things Indigenous. They are asked to sit on committees. The departments receive funding increases and accolades for their efforts. All of this, done, conveniently, without the need for actual Indigenous perspectives.

Moreover, I wonder how the pursuit to integrate “Indigenous content” into all classrooms is rooted in a desire to undercut the growing strength of Indigenous Studies programs, still the home of most Indigenous faculty on campuses. For me, Indigenous Studies is a space where like-minded people can come together to learn, plan, rest, and build strength. (Which is exactly why our gatherings have always been cause for settler concern.)

Finally, the desire of Canadian universities to play a role in “reconciliation” by incorporating Indigenous content and appealing to Indigenous students is driven by corporatization and investments in extractive industry. If they give us some programming, the logic goes, perhaps we will stop complaining about their storage of nuclear waste in our communities.

Indigenous Philosophers are accountable to their communities

Indigenous faculty and students are challenging the way this course is presently taught, but little has been done. The justification that forms a fortress around ignorance is “academic freedom”.

In the case of perpetuating incorrect history about Indigenous peoples, understand that your academic freedom has a body count.

We heard comments that this professor’s class was helpful to the cause of Indigenous Philosophy; that we should be grateful anyone was showing interest. This was followed by a suggestion that the way forward was for Indigenous professors to “work” with philosophy professors. A Nehiyaw professor objected, “Why would we spend our time teaching other people how to teach our subjects? And for free?”

As Vine Deloria, Jr. writes,

“The researcher has the luxury of studying the community as an object of science, whereas the young Indian, who knows the nuances of tribal life, receives nothing in the way of compensation or recognition for his knowledge, and instead must continue to do jobs, often manual labor, that have considerably less prestige. If knowledge of the Indian community is so valuable, how can non-Indians receive so much compensation for their small knowledge and Indians receive so little for their extensive knowledge?”

— Vine Deloria, Jr., “Research, Redskins, and Reality”3

To paraphrase another Indigenous faculty member, “If I walked in and decided I wanted to teach physics, they would laugh me out of the office. So why is it that this university is allowing someone to teach Indigenous content without the proper qualification?”

The Maintenance of White Supremacy

To quote philosopher Dr. Nathaniel Adam Tobias Coleman, “the effect of #whitecurriculum = we have imbued white male writers with the power & authority to speak for everyone.”

It is white supremacy to believe that non-Indigenous people are automatically more capable and qualified to articulate Indigenous histories, worldviews, and stories.

White supremacy is a white professor deciding, one day, that he’d like to teach Indigenous Philosophy. He is allowed to teach the class and given multiple platforms, including an upcoming departmental colloquium (colloquiums are mandatory for grad students).

Now, wouldn’t it be something to invite one of the many brilliant, accomplished, world-renowned Indigenous scholars on our campus to speak to this mandatory-attendance event? (Obviously, compensation would need to be provided. It is never the responsibility of invited Indigenous scholars to share knowledge to outsiders for free.)

Here’s the thing: even if Indigenous people were to spend our entire lives trying to explain our philosophies to settlers (this would be a great plot line for a horror movie set in Nehiyaw hell, by the way), they still might not get it.

Not only was the classroom content I described above inaccurate, but silly, as well, demonstrating a basic lack of understanding regarding the ways our communities operate. As Thurman Lee Hester Jr. and Dennis McPherson write in “The Euro-American Philosophical Tradition and its Ability to Examine Indigenous Philosophy”, “…to operate within the paradigm of Euro-American philosophy would mean that you are necessarily cut off from any real understanding of Indigenous thought.”4

This is the worst accusation of all for a white male philosopher: the suggestion that he cannot know something, and further, to point out that others have knowledge he might never be able to have. Not as a result of biology (!!!), but as the result of a redefinition of knowledge, giving weight to embodied experience; a recognition of Indigenous epistemic privilege.

Fundamentally, an unwillingness to acknowledge the expertise of Indigenous intellectuals is an unwillingness to concede space, privilege, and authority.

We are our own best wisdomkeepers

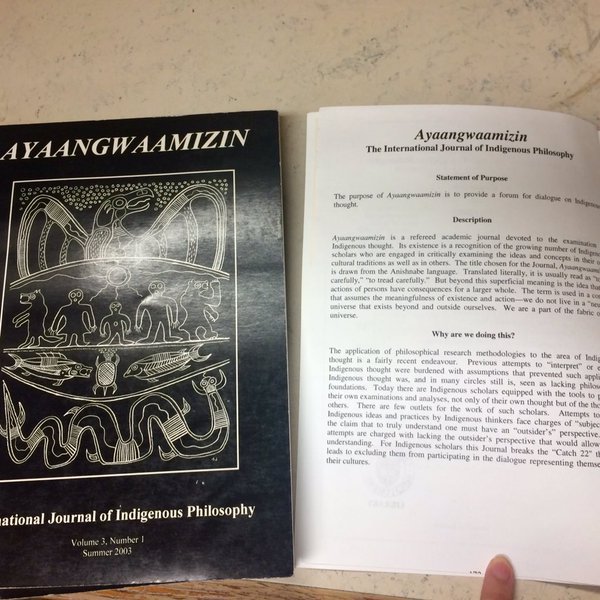

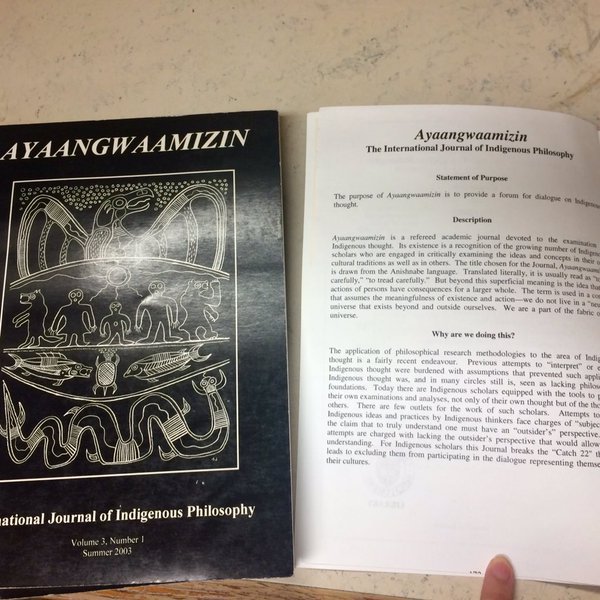

I want to give credit to Thurman Lee Hester Jr. and Dennis McPherson, whose work in Ayaangwaamizin: the International Journal for Indigenous Philosophy perfectly articulates why we are right to be uncomfortable if the “best person for the job” always happens to be a white man:

Even if workable research methodologies can be developed, there are still serious problems that make Euro-American examination of Indigenous traditions harmful.

The most serious is the potential for a scholastic “conquest” of Indigenous philosophy. Any academic book or university class carries with it the imprimatur of authority.

To the extent that these books are authored by Euro-Americans and these classes are taught by Euro-Americans, there is the potential for them to be perceived as the authorities on Indigenous philosophy. This tragic irony is already well underway. Many Indigenous people are reading these books and attending these classes, seeking to understand themselves and their histories. Though some do so quite critically, many assume that these books and classes would not be offered if they were not authoritative.

The damage done to people who believe this is difficult to describe, but can be devastating.

To believe that your own people are not their own wisdom keepers is horrific.5

My aim in writing this isn’t to provide lessons for white educators and administrators to become better at teaching Indigenous content, or to defend the total erasure of Indigenous content by excuse of ignorance. The centering of Indigenous knowledges in universities is important, and it must be done right. If the foundations of the settler colonial state are not challenged, the incorporation of so-called “Indigenous content” into classrooms is a method of continuous recolonization; furthering claims of ownership and authority over Indigenous knowledges and Indigenous lands.

As Jeff Corntassel writes, “Being a warrior of the truth is not […] about mediating between worldviews as much as challenging the dominant colonial discourse. It is about raising awareness of Indigenous histories and place-based existences as part of a continuing struggle against shape-shifting colonial powers.”

At the same time, respect that Indigenous students are regularly burdened with the task of “being a warrior” as we navigate through colonial institutions that force our disappearance through racist curriculum, only to hear “but we gave you Indigenous content, what more could you want from us?”

It’s important to remember that colonial educational institutions have never been the main method of preserving our knowledge (though we deserve to be safe in these spaces if we choose to be in them, nonetheless).

Our ancestors were imprisoned and even killed for practicing our knowledges, and yet, they persist.

This summer, I heard stories of how the land overlooking kisiskâciwani-sîpiy, where the University of Saskatchewan currently stands, was a gathering place for centuries.

Strange, then, how much it upsets folks when we burn sage and sweetgrass in offices and classrooms.

I heard stories from elders of how Métis and Nehiyaw mothers would construct improvised sweat lodge ceremonies using rocks heated in a frying pan, with blankets thrown over tables. The trick was that it needed to be swiftly dismantled if the Indian Agent were to come to the door.

Kinisitohten?

Now, do you understand?

1.↩ Thurman Lee Hester Jr. and Dennis McPherson, “The Euro-American Philosophical Tradition and its Ability to Examine Indigenous Philosophy” in Ayaangwaamizin, Vol. 1, No. 1, 1997. p 6.

2.↩ Natives and Academics: Researching and Writing about American Indians. Ed. Devon A. Mihesuah. University of Nebraska Press (1998). p. 13

3.↩ Mihesuah, p. 9.

4.↩ Hester and McPherson, p. 6

5.↩ Ibid.

Thanks to Dr. Rob Innes for helping with last-minute edits (and keeping me accountable)