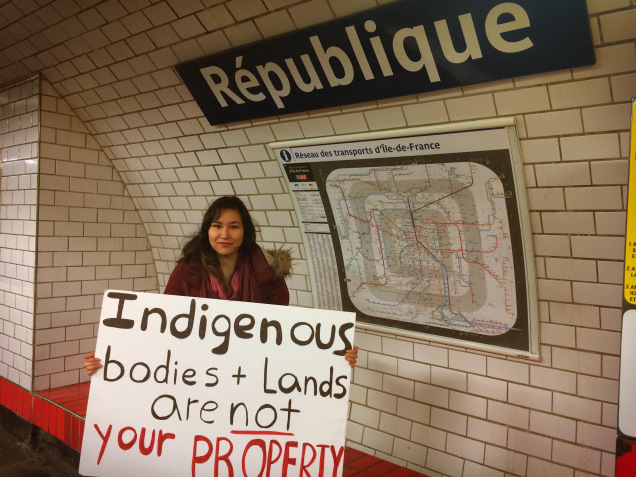

Content Warning: sexual assault; Indigenous Feminist anger that cuts like the lead riff in “The Trooper”

My optimism wears moccasins and is loud.

My optimism sometimes wears moccasins and is always loud.

As a Nehiyaw girl growing up in a small prairie city in Canada, I got into punk, hard rock, and metal music early on. My “rebellious phase” was spent at the local goth club between the ages of 13 - 15. Fortunately, the rebellion never involved drinking or drugs or sex. I didn’t have my first drink until I turned 19; my first kiss (with a boy…) a few months earlier. My vice was loud music. I grew up with other Indigenous kids who loved and lived metal music, and I have yet to outgrow that love.

Paris and COP 21

On a bridge over the Seine for the #Canoes2Paris action led by Indigenous people

I spent December in Paris for the United Nations COP 21 climate conference. In the context of global climate catastrophe, metal is the only honest soundtrack.

“We’re standing here by the abyss / and the world is in flames”

- Ghost, “He Is“

Hey Brown Kid!: You are inheriting a world that the powerful, rich, and greedy are fucking up. You have no money. You are told at every turn that you have no power, no chance: so you might as well have a furious soundtrack.

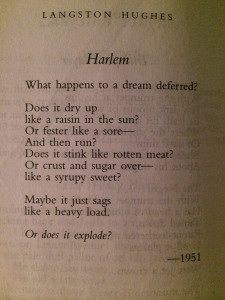

a half-removed poster for the Paris December 7th climate march in a metro station

Metal isn’t (necessarily) all about nihilism. The alternative to giving up is tending to the anger and learning from it. The alternative is coming to the realization that anger is the only humane reaction to injustice.

The trouble with cultivating anger is that it builds up inside your body, and it can rip you into pieces. Indigenous youth understand better than anyone that the cost of built-up anger with no outlet is drugs, self-harm, and suicide.

There is a stunning Icelandic film called Metalhead (Málmhaus), about a young woman who lives in a small rural community and embraces metal music as a way to confront death and hopelessness. The final scene is iconic, and will turn you into a puddle of melting corpsepaint if you, too, have headbanged in your room to Symphony of Destruction. The film’s themes translate well into the current realities of so many Indigenous communities.

I remember once, an old môniyaw professor asked me to send him an example of “your people’s music” after a conversation where he assumed the only instrument we used was “simple drums”. I sent him Biipiigwan (yes, that’s Anishinaabemowin).

Loud music is a fantastic traditional medicine.

The Show

[Ghost at La Cigale]

On December 7th, I went to see a concert by one of my favourite metal bands, Ghost.

I have a history of traveling in the pursuit of loud music. Running away from the incapacitation of depression exacerbated by staying still - running toward loudness, speed, feeling, and life. I kept an eye out for other metal shows in Paris at the same time but was disturbed at the possibility of walking into a white supremacist metal show. Being a Brown or Black metal fan, anywhere (but perhaps amplified in Europe) means the risk of unwittingly walking into a literal neo-Nazi concert.

Ghost’s singer, Papa Emeritus III, adorns himself like a demonic pope draped in velvet (…stay with me, now) while the other musicians wear variations of dark cloaks and masks. The identities of the musicians are hidden.

The lyrics mock religion, wealth, and worship. Something about the ghoulish aesthetic resonates with me, unsurprisingly, given Canada’s legacy of church-run residential schools stealing Indigenous children from their homes. Metalhead has similar themes.

The concert was at La Cigale in the 18th arrondissement, a short walk from metro station Barbès – Rochechouart. The show had sold out months earlier, so I walked around the venue to find a ticket scalper, preparing to struggle through a shady transaction in a second language.

I first saw him standing on the street corner, texting on his phone. One of the guitarists, who I recognized by his distinctive hair and his jeans - I think most musicians have that same pair of well-worn tour jeans. I walked up to introduce myself. Surprised that I had recognized him, we went into a bar nearby and had drinks.

I asked him how he was doing. He replied, “I’m fucking exhausted. We’ve been on the road for months.”

Explaining that I was in town for the climate conference, we talked about Sami politics and the environment. We talked about the similarities in landscapes and weather in Sweden and Canada; the isolation of small towns, the love of metal. Even in his exhaustion, he was kind and warm.

———

“It’s Paris, so they line up so neatly and always right on time.” No one in line for the concert recognizes him as he walks past; or if they do, they’re too Parisian cool to admit it.

Heading into the venue, I thought of the times I walked through graveyards in the middle of the night, with friends and a flask of red wine, listening to his music. I thought about telling him. I didn’t. I tried to be Parisian cool. (Cree taciturn?)

The After Party

“In the night / I am real”

- Ghost, “If You Have Ghosts“

The after party was at a bar called “The Mayflower” - the name of an infamous colonial ship. I cringed and laughed and complained. I drank absinthe and felt light on my feet, even though I had been dancing the whole night. Even though we were in a bar called “The Mayflower”.

That’s the thing about Paris. No matter how much I wanted to lose myself in the beautiful surroundings, I was unable to fully relax in such a hyper-colonial space.

Paris is a city that once had human zoos - where Black and Indigenous people were taken and displayed for the entertainment of gawking Europeans.

Paris is a city that displays colonial conquest in its museums, refusing to return ceremonial objects and even human remains to the Indigenous nations from which they were stolen.

So, forgive me for the absinthe.

I said au revoir and skipped off into the night, dancing over cobblestones to catch the metro home.

In Transit, 1

I saw this poster in the metro stations: a government advertisement promoting travel to Canada. The photo shows a vast, snowy white landscape with huskies pulling a sled. The caption reads: “Explorez sans fin / Canada / Keep exploring”. An advertisement of terra nullius - the notion of unoccupied, unused land which was invoked at contact to justify colonization of North America.

When I talk about colonialism, extractive industry, and climate change as having direct impacts on the bodies of Indigenous women, I don’t mean any of it as a metaphor.

———

There is something about the intersection of patriarchy and colonialism that gazes upon us in our moments of freedom and decides it will try to steal that, too. Europe’s history of colonizing (the Indigenous lands now known as) Canada is not something of the past that has vanished. Empire requires constant maintenance.

In the metro station, I was sexually assaulted.

When the man chose to randomly attack me he did it while I was in transit - on my way home from a concert by one of my favourite bands.

When he chose to attack me, I had just finished a drink with friends. I wondered if my blood alcohol content would be printed as a headline if I went missing.

When he chose to attack me, he became angry as I repeatedly pushed him away and refused him access to something that wasn’t his.

As I push the unwelcome white hands of this man away from my brown skin in a European capital, I push back on terra nullius.

In my refusal / I am real

All those times I said NO, yet he still doesn’t seem to understand - his doctrine of discovery is worthless on the surface of my skin. I was here first, and here I remain.

Yelling “no” in his face, the words hit my throat hard, the same way it would feel a few days later to yell “no” at rows of gendarmerie - French riot police - lined up with their rifles and shields to protect oil companies.

I ran up the steps and hit the emergency call button. I was too flustered to work my way through any intelligible French, so the man on the other end did not understand me. My attacker ran away. (Later, when I tried to report it to the police, no one spoke English so I was turned away. The next time I went back with friends who spoke fluent French, but the station was closed.)

I exited the metro station, expecting him to attack me again from behind every corner of the winding tunnel. I gripped my phone with its dead battery and thought about how best to use it as a weapon.

———

In response to the extent of gendered and sexualized violence we faced on the streets and in the conference centre alike, some members of our group suggest we do not roam the streets alone; that we implement a buddy system.

In response, I hop on a train to Belgium the next afternoon, alone, without telling anyone until I am across the border.

In Transit, 2: Antwerp

[On the train from Paris to Antwerp]

You are cast out from the heavens to the ground

blackened feathers falling down

You will wear your independence like a crown

- Ghost, “From the Pinnacle to the Pit”

I am happiest when I am moving; something to do with the histories of migrations in my blood.

One of the hardest things to learn as a young Indigenous person is slowing down. How do I force myself to be patient in the face of constant devastation? Why would I slow down when I might not get the chance to grow older? So, the speed of the train hurtling out of France and that loud, fast music in my headphones feels like freedom.

Upon arrival in Antwerp, I realized I had absolutely no knowledge of the Dutch language. The sudden, total immersion was frightening and exhilarating.

[Antwerp]

I navigated my way to the show at Muziekcentrum, where I was on the guest list. 13-year-old me would think I was so cool. I danced unabashedly, learning quickly that Belgian metal crowds are apparently very polite and barely move.

The show was magic; the loudness was medicine.

[Ghost]

I wanted to stay and say thank you. Thank you for your music. Thank you for helping me find freedom and anger in the face of devastation. But I had to catch a train back to Paris.

Just keep moving.

Travelling Home

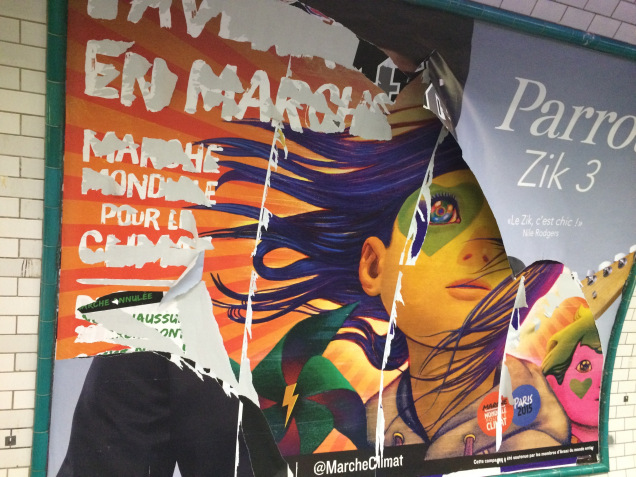

[reclaiming transit: in the République metro station - thanks to Katie for helping me with this photo]

“I can feel the thunder that’s breaking in your heart /

I can see through the scars inside you”

- Ghost, “Cirice“

As Indigenous women, how do we talk about sexual violence in a way that allows us to own our vulnerability? How do we prevent our stories from becoming consumed by colonial voyeurism in nations that thrive on making us vulnerable? I want to confront how violence against Indigenous women is presented as disconnected individual narratives, blaming women who put themselves “at risk”, rather than as a systematic necessity for the maintenance of settler colonial states.

Just as understanding histories and impacts of colonization is relevant to understanding Indigenous people, sexual violence is a devastatingly usual story in the lives of Indigenous women. But it is never our only story. Iskwewak (Indigenous women) are not reducible to narratives of conquest.

I read an interview where Henry Rollins says, “My optimism wears heavy boots and is loud.” My optimism wears heavy boots, sometimes moccasins, sometimes bare feet, sometimes skipping on cobblestones, sometimes on the prairies; my optimism is fucking loud. Raining Blood loud. War Pigs loud. Forever My Queen loud. Am I Evil loud.

I dream of Indigenous women and girls being safe & free in our own bodies and wherever we go in the world. But “safety”, in the context of global climate catastrophe, means cultivating enough anger as motivation to destroy extractive systems that will kill us unless we kill them first.

Surviving as a Native girl, daring to walk down the street alone at night: that’s a revolution. Listening to heavy music and dancing and drinking and being angry and loud, refusing to let violence rob us of wanderlust: that’s my revolution.

One day we’ll get that freedom. Just keep acting it out until it’s real. Just keep moving.